What it’s like to be a judge

Updated: August 2024

A remarkable podcast provides two perspectives, from this century and the last, on what it’s like to be a judge in British Columbia. The combined wisdom of two judges, their shared experiences, and the respect of one for the other make this podcast episode both interesting and moving.

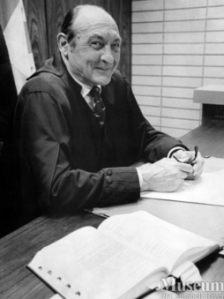

Roderick Haig-Brown

Roderick Haig-Brown was the consummate British Columbian. He is respected at home and abroad as an author, fly-fisher, conservationist, and magistrate.

Born in England in 1908, he worked as a logger on Vancouver Island and in Washington state in his twenties. He returned to England, published his first book, and then came back to Canada, settling in Campbell River in 1931. Earning a living by logging, trapping, guiding, and writing, he married Ann Elmore and they bought Above Tide, the house where they brought up four children and lived for more than 40 years.

Around 1940 (sources provide different dates for events in his life) Roderick Haig-Brown was appointed a magistrate. “I was the only guy with the time and education for the job”, he’s reported to have said. He served for three decades as a lay magistrate and, after the Provincial Court was established in 1969, as a Provincial Court judge until 1975. He died in 1976.

His achievements are stellar. In 1974 Canadian poet Al Purdy wrote:

“He’s so respected by other people that I felt incredulous when talking to them, and said to Haig-Brown himself when I met him, “You ought to have a halo, an angel’s halo quivering over your head.”

The catalogue of Haig Brown’s achievements runs on like a roll-call of honours. He’s written some twenty-five books, all but one still in print, and considers himself a writer above all else, although he hasn’t written a book in ten years because of his duties as a judge in Campbell River.”*

Although he wrote novels, children’s books, historical dramas, essays, and articles, Judge Haig-Brown is most famous internationally for his books about fly fishing. For example, the website of a fly-fishing museum in New York state includes him in its Hall of Fame, saying:

“Blessed with a graceful pen, he put words to deeds and actions that the non-angler could not only understand, but also truly appreciate.

He penned almost 30 books, including such noted works as A River Never Sleeps and the remarkable book series: Fisherman’s Spring, Summer, Fall and Winter and wrote innumerable essays and articles for outdoor magazines and journals.

He pioneered a fundamental environmental awareness and appreciation for the beauty and wildlife of the Pacific Northwest amongst the populace of B.C., which ultimately helped to preserve the precious resources in the Campbell River watershed, the Adams’ River steelhead runs and king salmon in the Nimpkish River.”

Many of his books are still available – some from their BC publisher, some as used books, and some as eBooks.

It’s impossible to do justice to Roderick Haig-Brown’s achievements in a few paragraphs. He was active in fishing and conservation organizations, served on the International Pacific Salmon Fisheries Commission and as Chancellor of the University of Victoria, and received a long list of awards and honours, including an honourary Doctor of Laws degree and having a university residence, a park, and a mountain named after him. (Mount Haig-Brown on Vancouver Island honours the conservation work done by Roderick and Ann Haig-Brown.)

The podcast

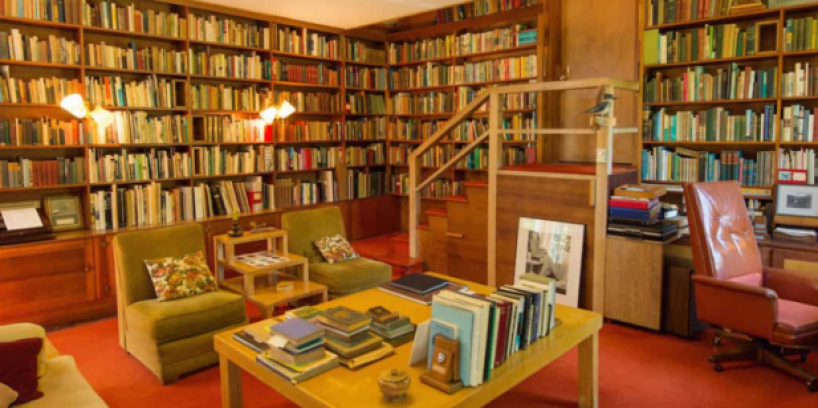

Called “Taking Measure”, the podcast is a project of the Museume at Campbell River and the Haig-Brown Heritage House (the Haig-Browns’ home now owned by the city of Campbell River and operated by the museum).

It explores Roderick Haig-Brown’s classic work, Measure of the Year: Reflections on home, family, and a life fully lived, with episodes based on the book’s twelve monthly chapters. Host Dan MacLennan interviews people familiar with different aspects of the author’s multi-faceted life.

The late Judge Ian MacAlpine

In the podcast episode for the month of May, then retired Provincial Court judge Ian MacAlpine spoke to Dan MacLennan about Roderick Haig-Brown’s life and work as a magistrate.

Their conversation revealed both links and parallels between the two judges.

Judge MacAlpine was born in Campbell River in 1936 and spent the next ten years there. As his father was a BC Provincial Police Officer, the family lived in the police station. The courtroom where Judge Haig-Brown presided was in the same building.

Beginning in his childhood, Judge MacAlpine read the magistrate’s books. He graduated from the children’s stories to the novels, essays, and fishing books.

Both men were writers. At age 11, during his father’s next posting, Judge MacAlpine and a friend started the first newspaper in Ocean Falls. He later left the University of British Columbia after a year to work as a newspaper and radio reporter in Saskatchewan for several years.

Judge MacAlpine’s interest in the law developed after he returned to Vancouver in 1961 as a court reporter for the Vancouver Sun, and for a time had an office in the courthouse at 800 West Georgia Street. He went back to university in 1968, graduated with a law degree in 1971, and was appointed a Provincial Court judge in 1979. For the next 25 years he worked as a judge, primarily in the Abbotsford courthouse.

Insights into a judge’s life

When re-reading Measure of the Year, Judge MacAlpine was struck by how well Judge Haig-Brown described the work of a magistrate or judge in court. “It’s still a very accurate and articulate summary of the role of a judicial decision-maker”, he said.

A lonely role …

In the podcast Judge MacAlpine commented on the way Measure of the Year revealed the loneliness of a magistrate - a person who worked more on his own than anyone else in the justice system. The magistrate had no jury, often no lawyers, and couldn’t discuss difficult decisions with anyone in his small community. The role of a judge today, especially in small communities, is still a solitary one.

An adjudicator’s sense of responsibility …

Judge MacAlpine also spoke movingly about the responsibility felt by judges who must make decisions that affect people’s lives profoundly, decisions that are irrevocable unless or until appealed. This was another aspect of a magistrate’s life described by Judge Haig-Brown.

The duty to apply the law even if you disagree with it …

He also discussed how Judge Haig-Brown acknowledged that he disagreed with some laws but nevertheless applied them because he had a duty to apply the laws enacted by government, a duty judges must still fulfill.

Ahead of his time …

Judge MacAlpine commented on the many ways in which Judge Haig-Brown was a progressive thinker.

As a magistrate he spent at least as much time resolving disputes out of court as in the courtroom. People would visit him at home for advice and informal mediation. Decades later, judicial mediation became part of standard court procedure in Canada.

Judge Haig-Brown was also ahead of his time in his empathy for Indigenous peoples, his use of restorative justice, and his commitment to conservation and protecting the environment.

Whether you're interested in BC history or want to know more about the art of judging and the life of a judge, this 56-minute podcast is definitely worth a listen.

* from Cougar Hunter in Starting from Ameliasburgh, the Collected Prose of Al Purdy

Photos from https://www.haig-brown.bc.ca/ courtesy of Museum At Campbell River

This page was printed from:

https://provincialcourt.bc.ca/news-notices-policies-and-practice-directions/enews/what-its-be-judge